Loot Box Query Response

Loot Box Query Response

As part of the Loot Box inquiry, we have provided some input from parents on their concerns about in-game spending and loot boxes, drawn from our Parent Generation Game Report. And also, information on the effect of loot boxes on children’s brains, which has been informed by the work of our Ambassador Dr. Linda Papadopoulos, a prominent psychologist.

Internet matters as an organization: Loot Box Query Response

We are an independent, non-profit organization created and funded by the industry to help children benefit from connected technology in a safe way. We invest heavily in understanding the views of parents and caregivers on a variety of online safety issues. We do this by surveying 2,000 parents of children ages 4-16 three times a year. In addition to that survey, we also hosted a 5-day online community for teens and parents to understand their gaming experience. All of these findings can be found in the Parenting Generation Game Report and the different methodologies explain why some comments have data points and some are sentiment conclusions.

Children and youth experiencing vulnerabilities are more likely to spend on loot boxes: Loot Box Query Response

Of course, not all parents are the same and the main factor in differences of opinion is the age of the child. However, interestingly for this research, there were statistically significant differences of opinion between moms and dads. Likewise, it’s important to note that vulnerable kids will experience online spending and loot boxes differently. Due attention should be paid to young people facing offline vulnerabilities, as they over-index as players who “often spend a lot of money on online games”. Cybersurvey data from 2019 indicates that while 15% of non-vulnerable children agree with this statement, the figures rise to 29% of children with speech difficulties, 27% of children with caregiving experience and children with anger problems and 26% of children with eating problems. disorders. These data points tell us that children with vulnerabilities are much more likely to often spend what they consider to be a large amount of money.

At the consultation, you ask a series of questions about damage related to loot boxes and online spending. Find our answers below:

Ask a. What are the damages and how do loot boxes cause them?: Loot Box Query Response

Over the course of our online community, parents told us that they were concerned about the normalization of gambling behavior through loot boxes; see Parent Generation Gaming Report, page 36. The nature of these purchases means that children are being introduced to a form of play very quickly. early age. Parents worry about the implications of normalizing these purchases and the kinds of gambling behaviors this could encourage for their children in the future.

“Again, loot boxes are very common in Fortnite and ‘bundles’ in FIFA are a similar product. It depends on chance how good the content is, which is effectively a form of game ”. Dad, with son, 13 years old

It’s worth noting that our research was completed before the gaming industry’s commitment to probability transparency in loot boxes was published, and we hope that parents will welcome this initial step.

Question b. If young people are affected differently from adults, and if so, how?: Loot Box Query Response

The loot box play element raises a number of related concerns for kids. Parents tend to teach their children about fairness and transparency in social transactions, about how to keep their word and do what they say they will do. That doesn’t happen in loot boxes; the transaction is unbalanced, rather than equal, and precisely because of the unknown element, loot boxes empower our children to invest for an intermittent reward. The risk here is that neural connections are formed in developing brains, which becomes habit. So while the reward provides a momentary excess of “wellness factor,” the flip side of dopamine is that it becomes habit. Add to this that games often reward competition and loot boxes can allow for faster game progression, and children, like adults, have a tendency to remember wins and forget losses, we have a toxic cocktail of unequal participation offering intermittent rewards, which becomes a habit. -formed in an environment of selective amnesia. That does not describe a situation where the interests of the child take precedence and their rights to safe online spaces are well respected. We would not go so far as to say that all online spaces should be created so that children as adults have the right to find enjoyment and escapism online, but children nevertheless enjoy the right to safe spaces.

The next area of concern is the value of intangible assets. Most in-game purchases are not physical items and therefore only exist within the game, for some parents spending on these games can be seen as a waste of money. Not having something tangible can be an unusual concept for parents to accept. One mother told us that she sees spending on games like “dead money because she (the daughter) has nothing to show for it.” If you consider an offline equivalent, creating a theme park where kids go alone and ask them to spend money to enjoy a more intense exhilarating ride, perhaps without a seatbelt, would raise some concerns, so it is good that we question them online too.

Parents are also concerned that children are dealing with pressure to buy when they do not understand the value of money and therefore may not be in a position to make informed decisions. These issues could be addressed if children were taught about stock consumption, perhaps through teachable moments about pocket money or gifts, but parents will want to do it their own way, not because an online game created one. situation to be addressed.

The persuasive design element of games and loot boxes should also be considered. Players are in a tug of war between themselves and the various ranks of psychologists who have developed the game, testing all the colors, sounds, and reward mechanisms to ensure that it is engaging. That is a significant amount of experience that we are asking our children to endure, in real time, with a world of peer pressure. It just isn’t a fair fight. How much better could it be if all those persuasive design elements were implemented for positive reasons. Not to rob the game of any joy, but simply to direct positive results, such as reminders to take a break every 30 minutes and perhaps time-outs after longer periods of play.

Question c. If the identified damages also apply to offline equivalents of gambling mechanisms, such as the purchase of merchant card packs.

While there are undoubtedly parallels between trading cards and online gambling mechanisms, in terms of the social status they confer, the key difference is the immediacy of the decision-making process required in an online game. There is no opportunity to reflect or even participate in buyer’s remorse since the pace of the game is so fast; The loot box is opened, its contents are delivered, and the game continues. Also, the nature of games as ‘social currency’ among teens means that there is no reasonable excuse not to buy the loot box; It’s not like you have to walk to a store to buy a pack of cards or ask your parents to buy it. one for you. You are there, in the game, often with your friends, making decisions in real time.

Question d. If the identified damages may also apply to other types of in-game purchases.

Parents are worried about all the expenses of the game. 46% of moms versus 39% of dads say they prevent their children from spending on games and 37% of parents say they should, increasing to 41% of parents of 4- to 6-year-olds and 44% of parents of children aged 6 -10 years. This is due to the reasons that we have already identified about uninformed consumption, the immediacy of decision making, investment in intangibles (which unlike offline experiences cannot be easily shared) and understanding the value of money. In addition, the schoolchildren told us through Cybersurvey about their spending habits. More than half (58%) of 11-year-olds never spend money on games. But 15% oftenthey spend “a lot of money” and 27% more have done it once or twice. Spending on games rises in the mid-teens, 14-year-olds are the most active with nearly 1 in 5 often spending a lot of money on online games, 28% more having done so once or twice. This pattern remains stable with age, as 21% of 16-year-olds often spend money on games, and another 26% say they have done so once or twice.

School-age gamblers frequently feel safer behind a screen than non-spenders (36% vs. 15%) and say ‘the Internet gives me personal freedom’ (56% vs. 25%) . They are more likely than non-spenders to say ‘I feel like other people when I’m on a screen’ (24% vs. 9%) and to say ‘my online profile is better than the real me’ (20% vs. 9 %). So maybe kids who frequently spend on games should be an indication that they may need some support with other issues in their lives.

The query also asked about PEGI ratings: Loot Box Query Response

As with everything related to parenting, there is a normative view, and there is the reality of parenting that, relative to PEGI ratings, is clearly outlined in this quote from a mother of a child. 11 years old:

“Alfie plays Grand Theft Auto online right now and it goes without saying that I am not entirely happy with the adult content. I have been reluctant to buy the game for him for several years, but now he’s at an age where all his friends have it and he would feel left out if he didn’t have it. “

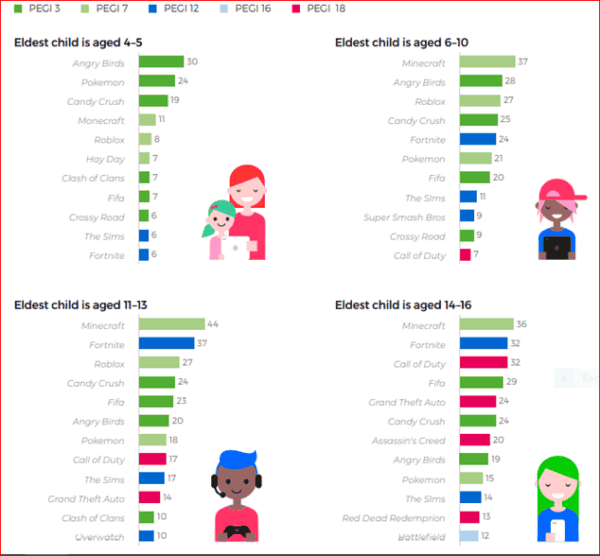

Of course, parents know that giving their children access to games made for adults, with all the content risks that this entails, is not ideal. And yet, in answer to this question: What games do you know that your older child plays on mobile devices or on PCs and consoles? Parents told us that they regularly allow their children to play games rated for older children. When we asked parents why they did this, the answer was a simple “how was it uniform”. Games are a social currency at school. If your high school aged child is not playing the right games, there is a real risk that he will be socially isolated at school, with absolutely nothing to contribute to any conversation outside of class.

This is not a positive decision by parents, it is the result of a hateful choice between allowing your child to experience content they don’t like or ensuring that your child is socially isolated at school. If there are 12 million children in the UK, this data suggests that tens of thousands of parents are voting for older content over and above social isolation.

If Call of Duty (PEGI 18) is played by 17% of 11-13 year olds and 32% of 14-16 year olds, the questions should be asked in two areas. First, how effective are PEGI ratings, and second, who should do what to counter pressing social pressure so that parents are not faced with this desperate decision? It’s not enough for game makers to hide behind ratings that they know don’t work and don’t address the compulsion built into the products they market that appeal to younger children. Perhaps, in addition to the items that are currently rated, the level of compulsion could be rated. Could there be a rating of the design metrics included to keep your attention or the intensity of the loot box entry to ensure that the percentage purchase rate is high enough to create a significant revenue stream? And if not, why not?